A Conversation with Carol Ross Barney, FAIA, HASLA

Carol Ross Barney has made an incredible and lasting impact as a leader in civic design and public architecture through her passion for inclusive design. Based in Chicago, Carol began her practice Ross Barney Architects in 1981 focusing on public projects. Also, in her role as an adjunct professor at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology, she has guided and mentored students, positively impacting the future of the profession. With her dedicated career as an architect and educator, Carol was awarded the AIA Gold Medal in 2023.

In this spotlight, Carol shares her approach to public architecture, emphasizing the importance of community engagement and collaboration in successful projects. She highlights that design is a process focused on identifying valid questions and needs, rather than just creating objects. Carol also discusses the monumental Chicago Riverwalk project and its relevance to other cities’ riverfront developments. She also gives insights on finding one’s voice in architecture, achieving work-life balance, and the role of confidence, particularly for women, in the architecture field.

Your presentation will focus on public spaces and how architects can contribute to making them exceptional through inclusive design. This is also the topic of your book, “The People’s Architect.” Would you talk more about how this focus on designing for the public really has become your life’s work?

“The People’s Architect” is interesting. It was part of the citation for the AIA Gold Medal. And I have to say, I’ve never used that term. I wouldn’t call myself “the people’s architect.” It sounds a little bit pretentious and pompous for me, but I do understand it has been really important to think about how projects get done because architecture is inclusive.

When I was in high school, I thought I would be an artist, and I would make art that made me happy, and then perhaps it would make someone else happy too. But their happiness was what was really not that important. And I thought to myself, this is great, but how do you improve the world like that? Everybody has an obligation to leave the world a better place than they found it. So, if you believe that, my follow-through is, well, then I’ll take my interests and my talents and I’ll try to do something that I’m good at that will make the world better.

And I landed on architecture.

I’ve always been really interested in space – making things like art is something that I’m pretty good at. Public space is the outcome of that.

The book is kind of interesting, because over the years, when they called me the people’s architect, I thought, well, this is great, but they’re missing a lot of people in this. It’s not just the role of one person, but how a project comes together, what types of champions, what types of communities, what type of integration do you have to have?

So that’s what I want to talk about.

That’s important, but I want to talk about the bigger universe. Some projects are super interesting because it might take one champion, and that single person can ignite a project and make it so much better.

Our theme is Reverb and Resonance. This next question pertains to how your project resonates with people and how it impacts not just the community locally, but also universally. It’s a bigger thing, like you said.

How do you make sure that your work or your voice resonates with the community?

Wow, that’s a good question. And it’s one of the things that my studio has been trying to develop for years and years. I always tell my students and people who ask – “Design is not a thing. Design is a verb, it’s a process.” The process is really focused on identifying a valid question, a valid need. And so, for me, making sure that your voice reverberates is that you find and have the right answer. Something will reverberate if you make an impact. Design is first finding the right question and then finding the right answer.

And if you do that, yes, it’ll be a project, an undertaking that remains in the community and helps the community and the world progress.

A project that we did years ago is the building that replaced the space that was lost when the Murrah building was destroyed in 1995. It was the first act of terrorism on American soil. We were commissioned to do this project. As soon as we got there, we found out that the people who were supposed to move back into the buildings, the ones who were on site the day that the bomb exploded, didn’t want to go back. They thought, “why do I want to go back to this place that I have such bad memories?”

The first thing we did for the GSA was a formal engagement; it was the first time we had ever done one. We spent a lot of time talking to the people who were in the building, to the elected officials of Oklahoma City, and to the public in general.

We were really intrigued by the process and the answers it gave us. It gave us answers, but I also want to say that it gave us support for the ideas that we eventually incorporated. We found out the dialogue and design process help you better identify the problem so you can have a better answer. In the end, it builds advocacy for the final project. This undertaking brought us to see it can be more than a building, it can be a park, it can be a plan, it could be an idea. It has advocates in the community, and that makes it reverberate through time. And it really amplifies the effect it can have on a society.

And then you mentioned engagement, which I think seems key to the whole resonating effect.

But it’s hard to do good engagement. I found that out too.In fact, I think that architects are not even architects (during engagement), because we’re like implementers.

Where communities go wrong with engagement is when they turn engagements into oppositions. I think that tension in the design process is a good thing, but when an engagement turns into just opposition, then it’s pointless.

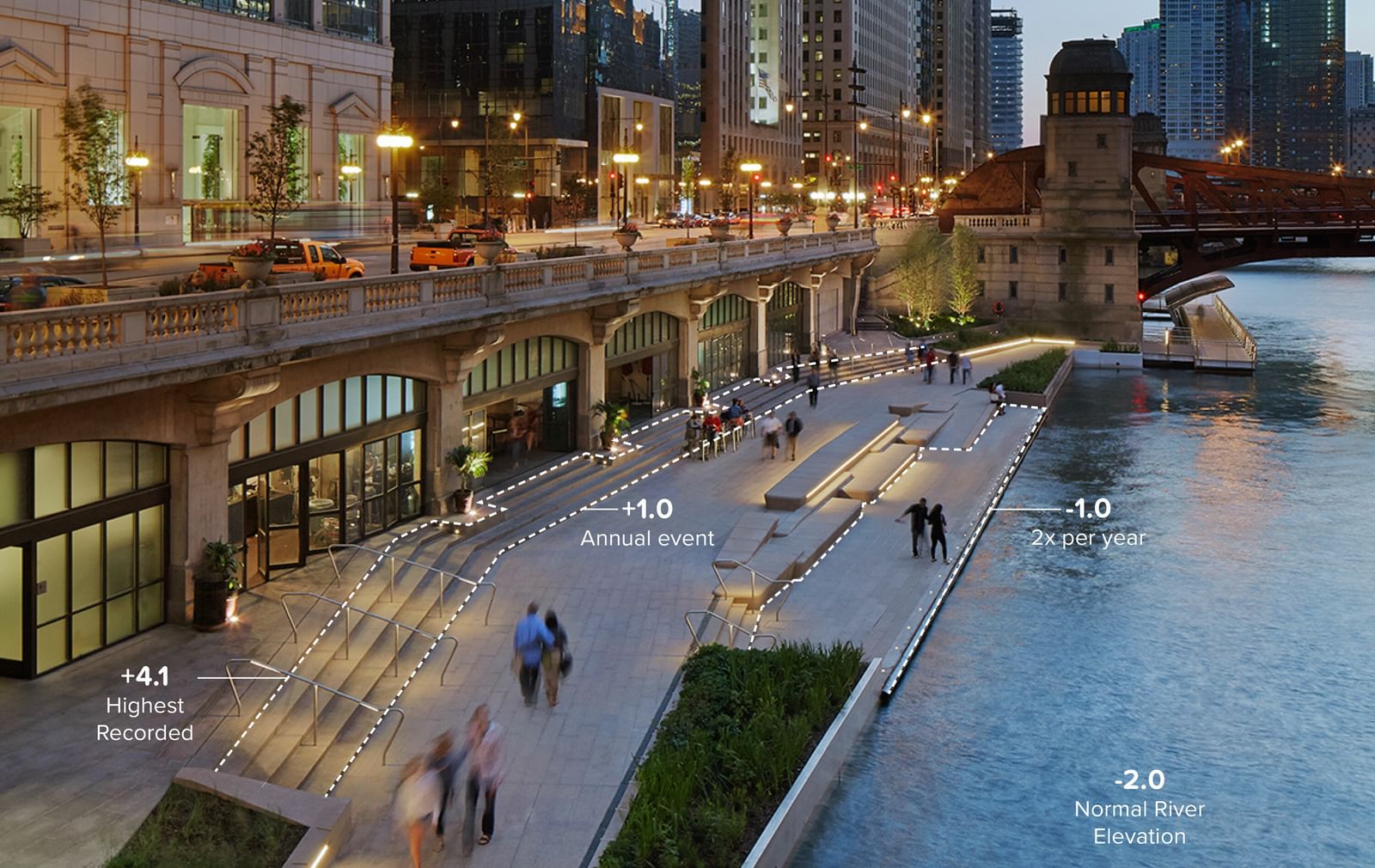

I wanted to also talk about your work with the Chicago Riverwalk. It seems like a very monumental project and has been it seems like it has been successful. I mentioned I lived in Memphis and we’re along the Mississippi. We have a pretty good riverfront, but still we’re trying to improve it. It’s been developed. Yes, and Nashville as well.

What have you learned when you have to reevaluate this as an urban asset? What do you think could apply to other cities like Nashville and Memphis that you’ve learned in Chicago? Or is it much too tied to the city and to the people that it’s a very unique response?

You know, you just used a really important word, and that’s “urban asset.”

And I think that what happened in Chicago is not one-of-a-kind. It’s not unique. And that’s why you’re seeing so many cities looking at their riverfront and really realizing that there’s value. And there’s a lot of commonalities here because I’m going to generalize here, but you could extend it, I suppose. I mean, especially west of the Mississippi and in the United States, cities are approximately the same age. And they were founded and developed in a period when transportation was so important and that was the primary source, primary value of rivers. That’s why a lot of cities are sited where they are. It was a geographical advantage that turned into an economic advantage. And especially over the last two centuries, while a lot of the dynamics of our economies haven’t changed, the role that the river plays really has.

And you put your finger on it – they are assets that have been undervalued and sort of forgotten.

What you’re seeing with the Riverwalk in Chicago is because of the timing of the project. And just because Chicago is still a big, important city. It’s been really lucky to be inspirational to other cities. Oh, yeah, our river is really great, too.

I’m not saying Chicago is the first one. There are predecessors. When we did the project, we started by looking at other inspirational river projects. You can look at the granddaddy of them all. You can look at the San Antonio River Walk. There are other cities that have built great urban parks and taken pieces of especially industrial infrastructure and resurrected it. But Chicago, I think, was lucky in a few ways.

I’ve learned over the years that projects have to be fortunate. It’s not just a star architect with a good idea that makes a beautiful project. There has to be the right economic climate. There has to be the right political and social climate for a project to be to be realized. And Chicago was lucky in a couple ways. There was other work happening downtown to infrastructure that had to be repaired. There was some money. In our case, the river was heavily polluted through the 1970s. The EPA sued the city of Chicago like they sued dozens and dozens of other US cities and said, clean water is important. Chicago, like a lot of cities, was forced to clean their water.

Originally, one of the reasons why Chicago is important is that it’s an easy tie between the Mississippi watershed, which is the watershed of Memphis and the Great Lakes watershed at Chicago. Those watersheds come so close, if you did a less than 10-mile canal, you could connect those watersheds. That was super valuable before trains; to get stuff when America was growing fast. And that’s why Chicago was so important. However, because we’re in that position, the Chicago River, for example, drains into Lake Michigan. It drains into the Great Lakes watershed. Chicago, the fastest growing city in the world, dumped all their sewage into Lake Michigan. That was a primitive sewage system and polluted all their drinking water. So very quickly they realized that this wouldn’t work. Everybody will die of typhus before too long. What they did is they reversed the Chicago River so the drainage from the city would go down the Mississippi, which was great because we didn’t drink from the Mississippi. Now, that didn’t do much good for St. Louis and other cities. By the time of the mid-20th century, people are saying, “Look, this is terrible. We can’t do this.” By the time we started working on the Riverwalk, the river was already clean, or it was clean enough that it wasn’t terrible anymore.

Funding public work has been really hard, and Chicago was lucky enough to have two mayors in succession that were really creative and had the right ties to fund the project. There are some local advocates in the community that also were great at making this project popular and feasible.

But it was easy for me, compared to what it could have been without those advantages. A project happens because a lot of things come together at the right time. Making those things come together, we have a responsibility to do that. But I think realizing that is important too.

That’s a lesson that Chicago has for other cities is that there are more parts than just thinking, “Oh, this is a great project. We’re going to do it.” You have to find the other pieces and fit them together.

This question has to do with mentoring and your career path. I put it this way because I’m currently trying to do this, but can you talk about finding your voice in architecture? Being unique in the field. You’re definitely recognized for that. Would you talk about that path, finding your voice?

I’ve been teaching for a long time now at IIT. And I get that question a lot – “What path should I take in architecture?” Sometimes it’s also sort of woven into life balance, which is an interesting topic. And I think finding your voice and life balance are probably the same question. You have to find what makes you happy. You have to find peace of life if you’re an architect.

Most architects are very idealistic. By the way, I think that in general, designers have to be idealistic, and they have to be optimistic and idealistic, because it’s, if you work, you jump out right away. You need those two things. I like architects a lot, first of all. I think that most of them are idealists and optimists. This is a vocation.It’s not a job. It’s not a 9-to-5. It’s not like checking out groceries or something. It’s something that they believe is important for the world. In any case, to find your voice, to get that balance, I think you have to find what makes you happy.

One of our strengths as architects is we’re generalists. We do a lot of things well. I mean, you can say, oh, I don’t draw like that guy over there, but we all draw well. Or I don’t have as many original ideas as that guy over there, but architects in general are bursting with more ideas than they’d ever need to have. Or the other one is like, oh man, I don’t have the patience to spend the time delving into the detailing like that guy over there, but you still know how to put a building together.

I think all architects like to make things. What you need to do is to find your joy among those things, because then, living it day-to-day, the other pieces fall in.

Sometimes we’re misled. Like it has to be one thing, like I have to work for a big firm or other certain accomplishments, but this is a really diverse field and you should find your joy and be really good at it. Then every day is fun. That’s my advice. Start out with the idea that I’m good at this and it makes me happy and then that confidence will help you find your voice, your balance.

You mentioned confidence and that maybe that’s the key thing. It’s like, at what point did you feel in your career you kind of gained that confidence? Was it after successful projects? What is the definition of what that would be for you?

Well, I wish I had an easy answer for that. I think it might be harder for women too. Especially given the place we are in right now in our history;in society. I’ve talked about imposter syndrome where I really have to live up to something because there’s so much expectation. I think women suffer from that in general. The other thing that’s true about confidence comes from opportunity, and opportunity, especially for women, has been the big miss. There’s not enough opportunity for women. I think there’s proportionately less opportunity for women than for men.

And I’m not saying that with a chip on my shoulder. That’s just the way it is. It’s where we are today. So, I think that confidence is a chicken and an egg story. It’s sort of like opportunity. You can’t have opportunity until you have a portfolio, and you can’t have a portfolio until you have opportunity. Confidence is a little bit the same. However, it is basically invested or coming from you.

If you really find what you like to do, you’ll find that confidence. When people are talking about stuff that they really love and are into, there’s a natural confidence that comes about it. So, finding that spot is really important because then it grows into other areas.

The question really has to do with the young minds because I think we’re focusing now on teaching kids and introducing them to architecture earlier in the pipeline, to inspire them when they’re more open to architecture. How would you describe architecture or what an architect does to a young mind? For me, it’s hard to simplify. How would you describe it?

Believe it or not, this question is related, but has AIA Memphis or AIA Tennessee had a lot of discussions about AI too? Because AI is about speed and “Will this take our jobs away?” as most people frame the dilemma. The answer is no. And the question with kids is what do you say to introduce what we do? The underlying question is how do you awaken young and old minds? How do you encourage people to think critically? When you think about having young people talk about architecture, it’s almost perfectly made to ask them to think critically.

You can start out with a conversation about, “Hey, do you like your house? What do you think about space? Do you like your bedroom? What’s the best thing about this park?”

Because it introduces the concept of critical thinking, how to make things, what is the problem, how to make things better. And that essentially is architecture. After that, it’s easy. You say, well, this is what the architect does. That’s how we affect that stuff. But because it’s something they interact with every day, if you think about it as asking them to think critically, it becomes an adventure for them. It’ll help them all through their life because I think that’s the key to AI too.

What AI doesn’t do is think critically. It thinks a lot. It’s way faster. It’s not that AI is thinking for you because you’re still left with the responsibility of thinking critically. That’s what’s unique about our talents as human beings – we think.

If you introduce that to kids, not only will they understand architecture and love it, and find it challenging and fun and full of discovery, but you’ll set up the whole world for them.

Photos Courtesy of Ross Barney Architects

OKC Federal Building, Photo Credit: Steve Hall – Hedrick Blessing Photography

Chicago Riverwalk, Photo Credit: Kate Joyce Studios

Chicago Riverwalk Water Level Diagram, Ross Barney Architects, Photo Credit: Kate Joyce Studios

This video conversation was AI transcribed and has been edited by AIATN for length and clarity.