An Interview with Nader Tehrani

Nader Tehrani is Founding Principal of NADAAA, an interdisciplinary practice with a body of work in infrastructure, urbanism, architecture, and installations. Tehrani is also the former Dean of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at The Cooper Union. Based in Boston, NADAAA fosters innovation through research and respect for the craft of architecture throughout the construction process. In our first Speaker Spotlight, Tehrani reveals much more about their collaborative design process and his perspective on the practice of architecture – encouraging discovery and reinvention.

First, would you give a brief description of what you’ll be presenting at this year’s conference?

I will be presenting a lecture called “The Animate Analytique”. The talk will speak to the relationship between architectural representation and its built reality. Specifically, I will examine the French Analytique drawing as a technique, and how that might be re-interpreted in an animate format to demonstrate the instrumentality of drawing as a prerequisite to architectural ideas. The presentation contains drawings, models, animations as well as built projects.

The theme of the conference this year is Reverb + Resonance. How do you ensure that your work or your voice resonates with your client or the community?

It is hard to ensure anything in an uncertain world, where differences in culture, opinion, and the immediacy of social media sways interpretations in any which way, especially at a time when attention spans are so short.

That said, to capture our clients/community’s attention, first and foremost, we “listen”. Listening to their voices guarantees that we prioritize their mission, culture, and agendas up front. It also allows us to show them the validity of their ideas as they become translated into formal, spatial, or material terms -something ‘architectural’, they cannot do on their own.

Beyond listening, we rely on the invention and precision of representational tropes to communicate ideas that would otherwise seem remote to clients…using diagrams, models, animations and other means to document how representation unleashes certain opportunities, beyond general ideas and beyond the literary.

We also study each culture, its geography, customs, and practices with a keen eye on imprinting that understanding into the design process, the organization of buildings and their details. Accordingly, we like to think of our designs not so much as a natural growth from their contexts, but rather a poignant response to them. To the extent that we understand local cultures, these responses can also reinvent that context; this is not only important for the discipline, but culturally relevant for them to instill their minds, who they are, how they evolve as a community, and how their aspiration may yet redefine them.

Your practice encompasses many disciplines and various scales with a research and process-driven approach. What have you learned most successfully contributes to discovering innovations or fostering innovation in your firm?

Over the years, our research has revolved around a few salient areas.

First and foremost, our early work took on the question of ‘means and methods’ to instill an argument that it is not sufficient for architects to communicate ‘design intent’ to their audiences.

Rather, by delving more deeply into construction trades, craft-based practices, and labor protocols, we have come to appreciate how invention happens when the architect knows as much, if not more, than the builders with whom they are collaborating.

NADLAB, the research branch of NADAAA undertakes many of these exercises, not only building models, but also mock-ups, and full-scale deployments of bespoke pieces in our projects.

Second, we have developed a number of projects dedicated to the single most overlooked element in contemporary architecture: the reflected ceiling plan. Knowing how the hung ceiling has come to house the key infrastructural elements of a building, such as the lighting, mechanical conduits and diffusers, sprinkler system and other life safety fixtures, among other things like acoustic baffles, we understand the ceiling to be pregnant with both practical and symbolic opportunities. Thus, instead of treating the RCP as an administrative duty, we have come to research it as a driving design force.

Third, with the unusual fortune of having won four schools of architecture, as commissions, we have also been able to research the ideas behind the ‘pedagogical building’. That is, we have explored varied precedents, models of learning, and the spaces in which they occur, and we have also identified emerging ways in which teaching and learning have forced changes on building design. Beyond the pedagogical building as a space of learning, we have also come to understand that these schools are, de facto, “didact instruments”. Because of the unusual literacy of their users, all students, faculty and alumni of architecture, the building -whether in failure or success, serves as a pedagogical tool, documenting the state of inquiry and exploration at a certain historical moment.

Beyond these themes, NADAAA maintains an open studio environment, where we encourage our team to remain “students”, with an openness to unlearning old habits, while learning new techniques and taking on new challenges.

All firms must deal with budget constraints. Without asking you to divulge too much about your practice, would you share how you structure your business or client fee proposal to create that room needed to be innovative?

We have a relatively low overhead. Thus, this gives us a bit of wiggle room to invest in research as part of the design process.

But also, because we have a set of ‘intellectual projects’ that serve as a continuum between our varied commissions, we strive to learn from our own research to determine their adaptability to new projects.

With a focus on forecasting, we are also always looking at ways in which to address proactively challenges that are often only detected in a later stage of the design. Accordingly, our work on means and methods is commonly done in the early stages of design, sidestepping the dreaded value-engineering phases many others face in later stages.

Would you share one of your built projects that best represents the culmination of your vision for architecture – where it should be and what the future of architecture should be?

I do not believe any one project of ours serves as a recipe for ‘what the future of architecture should be’. As an academic, I invite competitive interpretations of disciplinary priorities, with debate being central to the driving of ideas towards unsuspecting destinations.

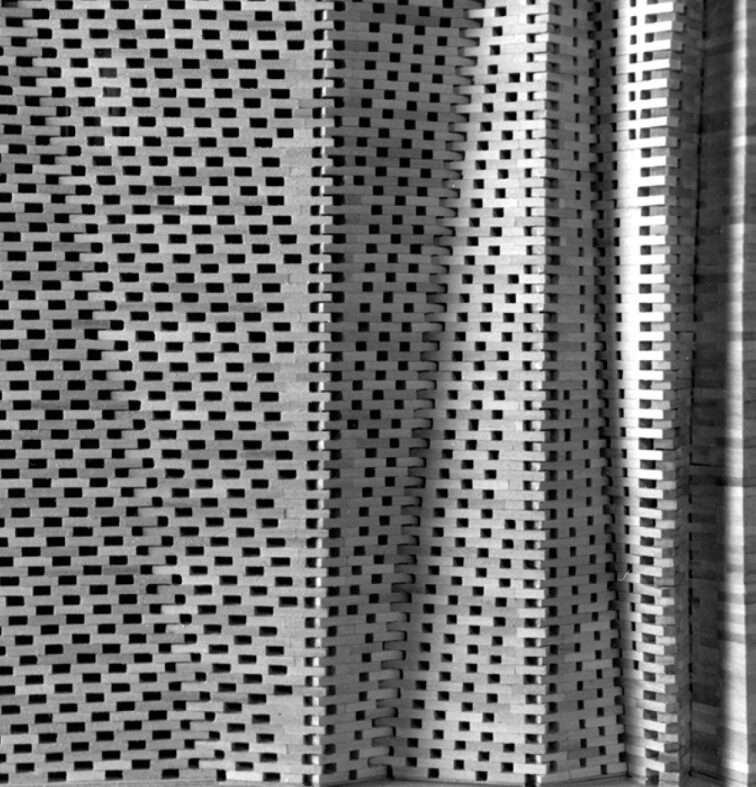

That said, if there were one argument that synthesizes one of our contributions to the discipline, it is the idea that our projects strive to establish a meaningful relationship between the “configurative” elements of a project and its “figurative” consequences. The configurative deals with the precise details of construction units and their capacity to make form: i.e., the differentiation between varied brick bonds enables different types of building organizations. The figure deals with formal issues inherited from the history of type, or shapes with semantic associations, or forms whose geometric descriptions allow for a reading larger than a focus on their construction details.

In Casa La Roca, we invented what we call a “variable bond”: an interpretation of the mortar joint as a variable dimension such that it achieves configurations anywhere from a Running to a Flemish bond. For Casa La Roca, this served as the ‘catalytic detail’ to create the curtain wall to the side of the house, and in turn, it also served as the DNA for the construction system of the Tongxian Arts Gatehouse, whose suggestive figure is precisely respondent to the configurations of brick that are its prerequisite. In these projects, the figure is the direct result of the configurations of tectonic units, and in turn, the material unit is a genetic seed of the many possible figures it unleashes.

Our profession has taken strides in influencing young minds earlier in the pipeline. It is not usually the dream job for elementary aged kids. Though your key experience has been in the university setting, how would you describe architecture or the role of an architect in a short statement that you find could encourage young minds to pursue architecture?

I would encourage young minds to become comfortable with two basic principles: the first is to abandon education as a way of cementing their idea of a profession, but rather to use the school as a way of preparing for “uncertainty”.

The second idea revolves around encouraging young minds to fail; that is, to play, explore, and inquire without the urgency of a ‘right’ answer, but instead to gain the pleasure of discovery in the act of making, and even failing in that process.

If anything, we encourage the next generation to become comfortable in a rapidly changing world where they might have to reinvent the discipline, rather than to conform to it.

Images Courtesy of NADAAA